Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It’s not the most mainstream topic we cover, but FT Alphaville Towers is pretty interested in the bond market impact of ETFs. After all, it’s becoming a pretty big deal, with another $120bn of inflows into fixed income ETFs already this year.

As Gregory Peters, co-chief investment officer of PGIM Fixed Income, told FTAV last year, ETFs have “transformed fixed income trading”, thanks to their underlying tech and rampant growth:

As a consequence the liquidity of the bond market has improved pretty significantly. It’s even more efficient than what we had before the global financial crisis, when we simply relied on dealer balance sheets. This utilises technology which will only get better, quicker, faster, and stronger. And I think that’s the transformational part of the ETF chassis.

Barclays’ “thematic” fixed income research team is just as fascinated by the phenomenon as Alphaville, and has been writing up lots of post-fodder research over the past year. The latest landed in our inbox shortly before the Trump tariff tantrum so we’re only getting around to writing about it now.

The tl;dr is that passive funds — ETFs and index-tracking mutual funds — now own almost a fifth of the entire US investment grade corporate bond market, and this is starting to affect how the market trades. Or in this case, when it trades.

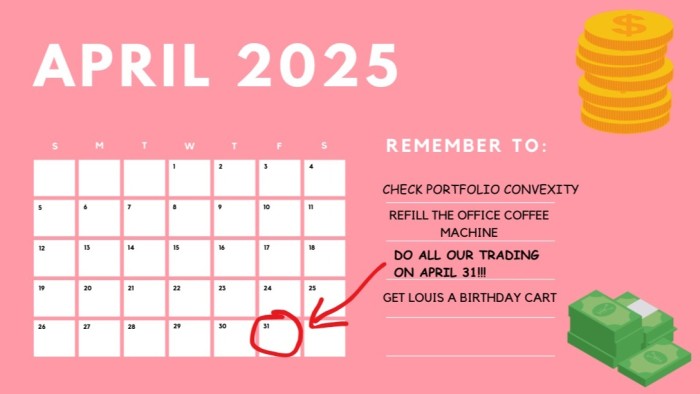

There has always been a modest jump in corporate bond trading volumes on the last day of the month, as many big investors rebalance their portfolios around then. But it has exploded in recent years thanks to growing passive funds rejigging their holdings.

Trading volumes in US investment grade corporate bonds is now on average 82 per cent higher on the last day of the month, compared to the up from about 25-30 per cent a decade ago.

The emergence of a month-end trading spike is primarily driven by the growth of passive bond funds. In 2013 they held just 5 per cent of the US investment grade credit universe, but today they hold nearly a fifth of the market, according to Barclays.

The bond market footprint of ETFs is still much smaller than that of index-tracking mutual funds, and Barclays’ report mostly deals with passive investing as a whole. But Alphaville is pretty sure that the dominant driver is the growth of fixed income ETFs, given the unique liquidity-nurturing characteristics of their creation-redemption process.

Interestingly, traditional active bond funds are now reinforcing this trend, by doing more and more of their own trading at the end of the month to take advantage of the increasingly bountiful pool of liquidity.

As Barclays’ Zornitsa Todorova and Andrea Diaz Lafuente point out, passive funds provide “predicable, programmatic liquidity” at the end of every month, which is attractive to everyone:

Because trades by passive funds are rule-driven and not discretionary, other market participants, such as mutual funds and hedge funds, can anticipate these liquidity flows and position themselves to exploit these predictable patterns. Over time, month-end liquidity has become self-reinforcing: active funds anticipate the predictable rebalancing by passive funds at month-end, leading to increased participation and trading activity. As passive funds have expanded their presence in the IG market, market participants now expect easier access to liquidity across a wider range of securities, resulting in even larger month-end liquidity spikes.

Barclays estimates that bid-ask spreads are now about 12 per cent tighter on the final day of the month, and the price impact — measured by the average daily price change relative to turnover — is 40 per cent lower.

These metrics are both markedly better than they were a decade ago.

So what does this mean for everyone else? Well, we’re spitballing here, but if the “liquidity smirk” in equities is anything to go by, it might mean increasingly abundant liquidity at the end of the day, and on the final day of the month. Liquidity beget liquidity, after all.

However, that in turn could mean that corporate bond markets become a tad more volatile in more fallow midday and mid-month periods, as investors herd where trading costs are the lowest. Are we seeing any evidence of that so far? Not that we’re aware of, but perhaps some helpful analyst could run the numbers.